Ten learnings from ten years as an agile business analyst!

Or, some things I learnt the hard way ...

Last month I did a talk to a Business Analyst meetup group.

The topic they chose (from my 6 suggested options): Mastering agile: 10 learnings from 10 years of working as an agile business analyst. Here is the blurb for the talk:

Hannah is an enthusiastic business analyst with more than ten years of experience working as a business analyst in delivery. […] Come along to hear about what life is like for a business analyst working in an agile delivery team and what makes delivery focused work different from other BA work. She’ll share how she approaches her work, her ten most important learnings from her time on the front line, and answer your questions about life as an agile BA

Supremely cheesy title aside, this was a really fun thing to do a talk about. This article summarises the contents of the talk. But if you prefer to listen to my grating kiwi accent, you can watch the recording of the talk on Youtube.

Here are the ten learnings so you can skip to the one of interest to you!

The ten things:

❶ Embrace not knowing

❷ Don’t talk for experts

❸ Analysis is a collaborative activity

❹ You only work with models

❺ There is no one right way

❻ Understand the big picture (but move small pieces)

❼ Presentation (and messaging) matters

❽ Politics beats “right” every time

❾ Make friends with the dark cloud

And last: You serve the team, not the BA gods!

And without any further ado, let’s jump in!

1. Embrace not knowing!

When you work as an agile business analyst, you are surrounded by experts.

You have experts on your team, and you are constantly interacting with experts outside the team. You watch them draw on their own knowledge and expertise to solve problems.

It is easy to feel like the odd one out. 😕

Early in my career, the desire to contribute like everyone else did drove me to chase the acquisition of knowledge.

It was a deeply unsuccessful approach.

Because not knowing stuff, and not being the expert in the room, isn’t a bug, it’s a feature of the business analyst role! To know everything about a topic is to be an expert. And being a subject matter expert is an entirely different role. And you can’t be both.

Business analysts find stuff out. That’s the core value-add! At our best we can walk into any situation and find out how things work. The only way you can really find out what’s happening, is by embracing the fact that you don’t know, and be comfortable asking questions.

Even when the questions sound dumb in your head.

So if you’re starting out, and feel like you are spending a huge amount of time confused and not understanding. Get used to it because this is as true for me today as it was back then!

I’m always the person who is saying “huh?”, and “I’m sorry but what do we really mean when we say that?”, and “just to make sure we all understand” …

Once I worked out that this was simply part of the role, work was much more enjoyable!

Until I made the next mistake 👇

2. Don't talk for experts!

When you’re the business analyst on a team your job is often to head out into the organisation to find an answer to a question and report back.

Sounds easy enough, no?

Well here’s the trap: When you report back, take care to not overstep.

What do I mean by overstep?

I mean that it is easy to assume the role of an expert. You’ve gone out and collected a bunch of information. You understand the info and the impact. You can see the basic pattern of how it all works. From there, it is easy to feel like you know what you’re talking about.

But you don’t.

Experts don’t just know a little more than you. They know A LOT more than you. They know the one pattern you asked about, and they know how that one pattern interacts with all the other patterns out there, and when the pattern does not apply.

Being a journalist is a great metaphor here.

When a journalist interviews a physicist, they don’t present the information as if they’re the expert, they explicitly acknowledge where the info came from, and, further, they would refer back to the expert should a question they face not align to precisely what they covered.

In other words, they’d say “we’d have to refer back to Mrs. Physicist for that info” rather than say “based on what I know, the answer is probably XYZ”.

Think like a journalist, not an subject matter expert. 🎤

3. Analysis is a collaborative activity!

It might be obvious to you by now that when I started out as a business analyst, I had a massive chip on my shoulder. Huge! I wanted to prove my value to the team, to the organisation, and to myself!

Because I thought I was responsible for ‘analysis’, I would try and get ALLLLLL the questions answered before the team even got close to a piece of work. I wanted everything to be perfect!

But while business analysts might be the only role with analysis in their name, that doesn’t mean that they are the only role that does analysis!

Over time I began to see a pattern. The earlier I involved the team, the better the analysis. And by better I mean more rigorous, more comprehensive, faster, and much much more likely to result in a better business outcome. This is why I am a huge fan of collaborative elaboration methods (including my all time favourite: Story Mapping).

And a happy bonus, taking a collaborative approach results in far less boring handover for me. It is way easier simply to involve your team in the elaboration and analysis process then it is to transfer all that information at then end (and only then find out where the gaps are).

There is one caveat to what is otherwise a good news story: making analysis a collaborative activity means that you have to be open to feedback. You don’t get the chance to polish something before people wade on in with their opinions and thoughts. That is not always fun!

But the outcomes are 💯 percent worth the ride.

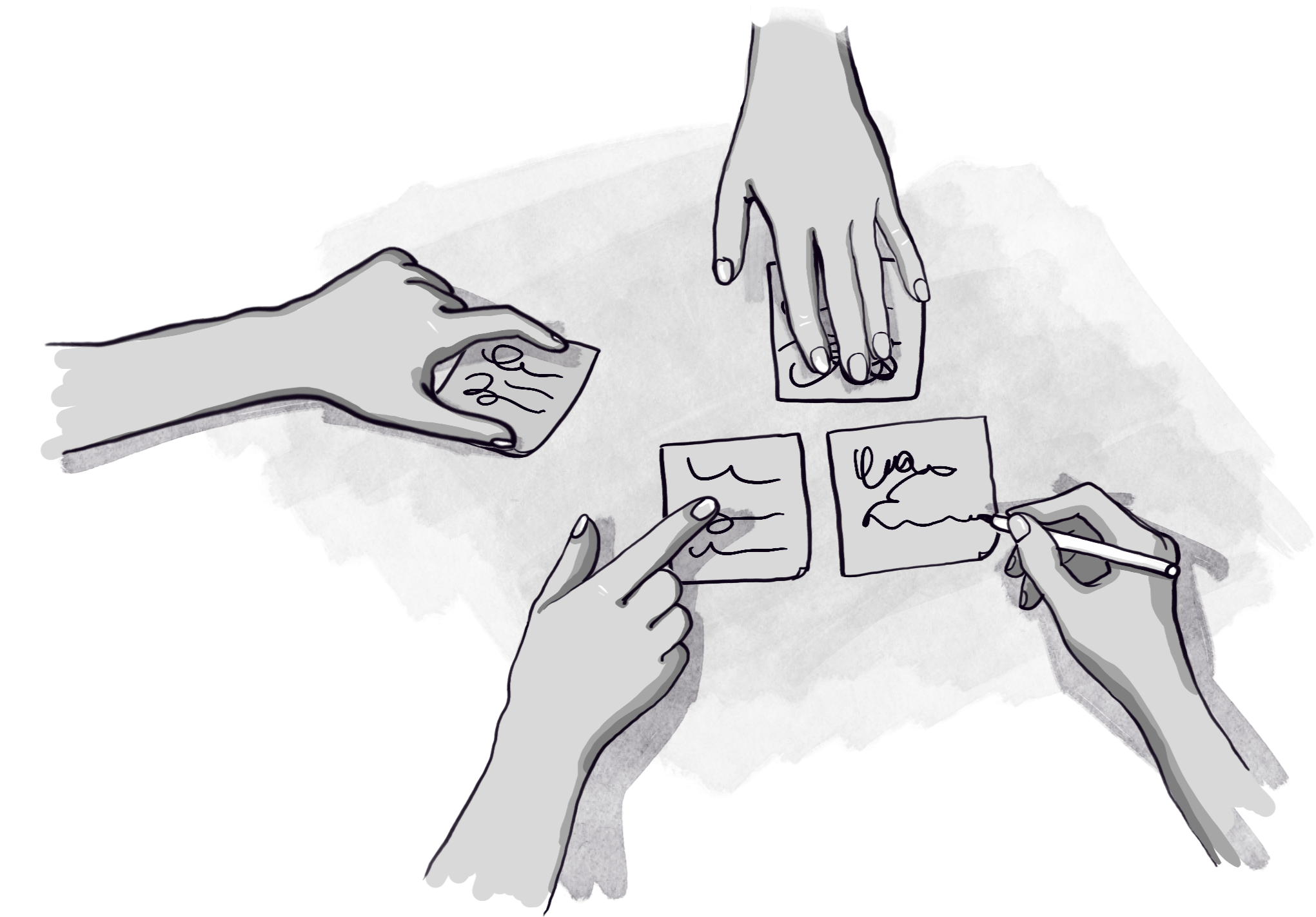

4. You only work with models

Good business analysts think that they work with reality, great business analysts understand that they only work with models.

Let me explain.

Requirements, process maps, user stories, options analysis … ALL the things that business analysts work with are models of the real world. We aren’t actually doing the process when we document it, we are modelling it.

👆This is a very important distinction.

Models make reality easier to talk about (which is often the point of the model).

But despite how important models are, they should never be the focus. You don’t model a process to produce a process model. You model it so that you can talk about it, optimise it, communicate elements of it.

The model is, and will only ever be, a summarised view of the world.

Understanding a model is not understanding reality. You want to keep your focus on the real world.

You are far closer to understanding reality when you not only understand the model, but also can also translate between different models while still maintaining the integrity of the representation. You understand it when you can model reality in different ways in order to communicate or highlight different aspects.

There is no one right way to model reality. Use case diagrams, user stories, process maps, and ability statements can all model and document the same reality.

I’ve witnessed many business analysts, when their model format is challenged, defend their format as “right”. Which, when you think about it, is a sort of insane position to take. Take your time to learn the difference between feedback on format and feedback on reality.

It will save you a lot of heart ache! 💔

5. There is no one right way!

I cannot count the number of times someone has told me, with utter conviction, that this way or that way is the right way.

They are lying.

They might not know that they are lying. They simply might not have had enough experience in different environments to know.

It doesn’t matter. It still isn’t the truth.

Every single organisation does things differently. Even those that obstinately practice the same delivery methodology do things differently! Sprint planning can be an all-day activity in one organisation, and an hour long session in another. Backlogs can include just product items in one place and all sorts of nonsense in another.

But it’s more than what we call things, and how we arrange the work: every single human system has it’s mores.

Best practice is optimised for everywhere, and thus mostly optimised for nowhere exactly. And certainly it has not been optimised for precisely the circumstances you are in. There will be reasons why they’ve ended up with the process and approach that they have.

The best thing you can do you simply ask: How does it work here?

And fit to that.

6. Understand the big picture (but move small pieces!)

This learning is more instructional than the others. It is more of a “this is the only reliable way I’ve found to work with complexity”.

Nowadays, it feels like every project and product is complex. Like real complicated.

And it’s usually too much to fit into one human brain.

I remember my first large programme. It was a point of pride that I knew everything on the backlog. Everything.

Which was, and I cannot emphasise this enough, a complete and utter waste of time!

Most of what we do is too big to hold in our brains at any one time. So you need to find ways to be able to dig into the detail, but make sure that the detail you are working it contributes.

How do you do that?

Well, first you go shallow but wide. Identify the boundaries of the project, but don’t get into the detail yet. You’ll have accomplished this, for example, if your project is a new online store and you have identified what’s in scope (the website) and what isn’t (social media and marketing).👏

Next, decompose that big picture into large chunks that make sense. For our online store, this might be homepage, gallery, contact us functionality, the shop itself, the cart and payment functionality, and a blog. These are all big chunks that together make up the whole, but are distinct enough to talk about separately. The trick here is to avoid going too deep. You don’t want a ton of ‘parts’ to work with. You want just the next level of detail down from the whole.

Once you have your chunks, prioritise them! Pick the chunk that is the most important, highest risk, or most work. The reason we prioritise is to make sure we’re working on the most important thing (remember: any of the chunks could get descoped!).

This is where you focus. Here is where you can dig into the detail safely because you know how it relates to the other big chunks!

This approach means that you understand the big picture, but are making actionable progress—without overloading your brain!

And the approach is fractal. You can repeat these 4 steps (identify the boundaries, decompose into smaller parts, prioritise the parts, and focus on one bit) at each level as you dig into the details.

There you go. That’s my approach to making progress in the face of complexity!

And while on the topic of responding to human limitations …

7. Presentation (and messaging) matters!

All the people you work and deal with are just that: People!

And being people, they have all sorts of their own human-related chaos going on. They are parents. They have deadlines. They have too much work. They’re juggling mortgages, their own boss, and their staff.

You will be much much more successful if you acknowledge that and make it easy for them!

And since a lot of what you do as a business analyst is to communicate stuff, I cannot stress enough how important presentation—and messaging—are.

The simple act of ensuring the most important details are highlighted, rather than expecting them to wade through all the minutiae, is an act of kindness. One that will be repaid ten fold in terms of genuine engagement, feedback, and support.

Don’t underestimate the power of a well-formatted, well-summarised, and well-structured piece of work.

And remember: a lot of what we do is journalism, so there’s an element of editorial selection for what the most important info is and how that information should be positioned. This is where you’ll be using your analysis skills. The best option, poorly summarised and sold, isn’t likely to land well.

But also keep an eye on the politics 👇

8. Politics beats “right” every time

In life, and at work, what is politically feasible will win voters and support over what is rationally the “right” option. It is depressing. It is frustrating. But it is certainly true.

If you’re not careful that is.

I learnt this lesson the hard way by naively assuming that common sense and rationality prevails. It didn’t in that situation, and hasn’t in many situations I have been in since.

This is not to say that you should simply surrender to the political powers. Do not! Do fight the good fight for what is best for the organisation, its people, and its vision. But you can only do that if you are pragmatic!

If you don’t understand and prepare for the politics, then they will own you. And you will be disappointed.

So understand and prepare.

If politics is a tank, then don’t arm yourself with a knife. Instead, get a F-16. 🚀 In practice, this means networking wildly, sharing broadly, and gathering heaps of feedback. And working with people in the business to understand the landscape that you are trying to change.

You want to know where the minefields are before you stumble over them.

9. Make friends with the dark cloud

There’s always someone. The grump. The person in the room who says that the project is going to fail. Who points out the problems and raises challenging questions.

They’re the dark cloud. ⛈️

And you should make friends with them. 👯♀️

Why?

Because polite society doesn’t tolerate grumpy people unless they have too. In polite society, grumpy or negative people are only tolerated if they are valuable. And in our line of work valuable means knowledgeable.

So, if someone is grumpy and saying negative things, but they are being tolerated by the team, then there’s a good chance that they just know more than you and the warm glow of opportunity has faded from years of watching initiatives fail.

It’s easy to hear the grumpiness, feel the negativity, and assume that the dark cloud simply wants the initiative to fail. But the truth is that if someone wants something to fail—and they’re not a complete idiot—then they might warn of issues once, but after that they will sit back and watch the train wreck occur. Followed by an “I told you so” along with “of course, no one listened to me”.

People who want an initiative to fail don’t keep banging their head against the wall trying to get others to take the issues and risks seriously.

So, rather than spot the grump and, like most people, strenuously avoid stumbling into the negativity. Put on your big girl/boy pants and go say hi. If I’m right, you’ll find out some of the biggest issues and risks that your project faces: risks and issues that will hurt you later

Don’t take the negativity personally.

You never know, they could turn out to be your biggest ally.

(CAVEAT: They could also simply be a grump and want the initiative to fail because they don’t want to change, but what I’m saying is: you should find out for sure.)

10. You serve the team, not the BA gods!

The last learning, but I think this one is the most important.

When I think about all of the things that I’ve worked on, I see a really interesting pattern:

There is absolutely no correlation between the how perfect my analysis process was, and the outcome we produced.

Some of the very best outcomes as a team were when the analysis was done in a crisis call, scribbled on the back of a post-it note, and documented in Slack. No fishbone diagram or fancy process model in sight!

The BA gods would not have been pleased with my work.

We all want our work to be as good as it can be. We all like it when our backlog is well refined, all the tickets have the same pattern, and we have created beautiful artefacts!

But none of that actually matters.

Outcomes do.

Worshiping the BA gods and perfect processes takes our attention away from focusing on actual delivery of real outcomes.

Stop chasing perfection; start focusing on your team.

You will have fewer pretty things to show the world, but you will be part of something better: Actual results.

How visualising my process has helped it

These learnings represent more than just nuggets of information that I’ve gathered. They are the insights that inform my approach to business analysis—a topic I have discussed in another article: Analyse, Connect, Do.

And that’s it! The ten most important things I’ve learnt from working as an agile business analyst in delivery! I hope that you find them helpful on your travels.

Hey, tell me what you think!

Please do hit me up on LinkedIn or by email if you have any feedback! I’m always up for difficult questions, and I’d love to know what you think of this article!